Blog Archives

The Aftermath…

Hailstorm: The Aftermath

By Bruce Rottink, Friends of Tryon Creek Volunteer Nature Guide and Retired Research Forester

This past June 16th a violent hailstorm hit Tryon Creek State Natural Area. Many plants in the forest sustained damage, but was it serious? How would the plants fare in the long run? What can we learn from this experience?

Some plants are tough!

Let’s take a closer look…

The most common type of damage was the shredding of plant leaves, and breaking of stems from the impact of the hail stones. In general, the leaves and stems that were going to die from hail damage, died quickly. For example, the severely injured leaves on the red elderberry (Sambucus racemosa var. racemosa) shown below were already grey-brown and crispy within two weeks after the hail storm.

The leaf shredding looked serious, and certainly didn’t do the plants any good. But, many of the “shredded” leaves persisted throughout the season. Two species that showed especially severe leaf damage were trillium (Trillium ovatum) and thimbleberry (Rubus parviflora). The photo below was taken 34 days after the storm. It shows a trillium “leaflet” which was brutally shredded by the hail. It hung on like this throughout much of the summer, finally turning brown on approximately a normal schedule.

Likewise, the photo below is a thimbleberry leaf taken exactly 5 weeks after the storm.

The persistence of the leaf tissue in spite of the shredding, is a testimony to the effectiveness of networks. The leaves of broad-leafed plants are typically based on a vast network of veins.

What do these veins do exactly?

-

A) physically support the leaf

-

B) deliver water and minerals to the leaf’s cells from the roots

-

C) carry carbohydrates (“food”) produced by the leaf to other parts of the plant

If you guessed A, B, and C, you’re correct! The key is that there are more than one vein serving each small chunk of the leaf. Thus if any one of the veins was broken by hail, water and minerals could be delivered to a specific cluster of cells via a different path. This network makes the leaf very resilient. The photo below is a close-up of the network of veins in a jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) leaf.

Just for fun, on the picture below trace the number of vein paths you can find to get from the major vein shown in the photo to the cluster of cells marked with the red star. (Hint: The first four ways are pretty easy to find.)

Persistent Petioles

The other major kind of impact damage was the breaking of stems and petioles (a petiole is the “stalk” of the leaf blade which attaches it to the stem). There were many amazing examples of stems and petioles that were broken, and yet survived. The broken petiole pictured below is on red elderberry.

However, the leaf beyond this break remained green and alive, as pictured below.

Some plants have a backup plan!

Some plants sustained irrevocable heavy damage, and resorted to their “Backup Plan” which is to replace the parts that were lost with new parts. Two of the many plants that used this strategy were the skunk cabbage (Lysichitum americanus) and red elderberry.

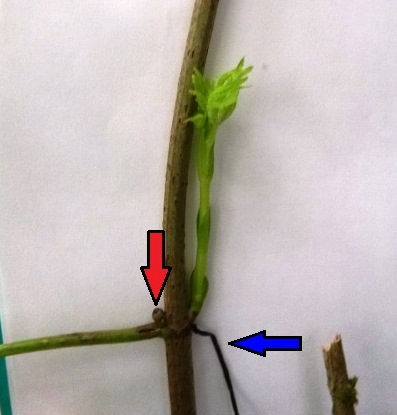

The hail was particularly hard on the skunk cabbage. In the photo below you can see a skunk cabbage plant taken 23 days after the hailstorm. The blue arrow points to a severely shredded skunk cabbage leaf’s midrib, and the red arrow shows a new leaf sprouting after the hailstorm. This leaf was not visible 4 days after the hailstorm. To be honest, I can’t say for certain this leaf would not have sprouted up without the hailstorm; however the fact that the skunk cabbage had not produced any new leaves for many weeks before the hailstorm suggests that this leaf is indeed “a child of the hailstorm.” At the time of this picture, the new leaf was 15 cm (~6 inches) tall, but being nearly vertical makes it look less impressive. By mid-September, the new leaf grew to 32 cm (just over one foot) tall. A second post-hailstorm leaf appeared later, and grew to 9 cm (about 3-1/2 inches) long. Both stayed green longer than the leaves present at the time of the hailstorm.

The elderberry plants exhibited a classical response to the destruction by the hailstorm, as illustrated in the photo below. As you can see, the tip of the elderberry shoot has been knocked off. In each leaf axil (the crotch between the leaf and the twig) there is a bud. Normally, the tip of the plant produces a chemical, auxin, which inhibits these buds from growing, and they would only sprout out the following year. However now that the tip of the plant has been knocked off, there is no more auxin to inhibit those buds. They are more likely to sprout immediately. For the elderberry, the recovery strategy, then, is to have buds which were being held for next year open early.

The bud (red arrow) on the left side has not sprouted, but the bud on the right side has sprouted, which is facilitated by the death of the leaf (blue arrow) on that side of the stem. If you view the growing shoot tip as “the leader”, this is the botanical version of

“the king is dead, long live the king”.

Another interesting example of recovery from buds was Pacific waterleaf. The visible Pacific waterleaf shoots originate from a rhizome (essentially an underground stem). While there was no real recovery of the damaged above ground shoots, fresh new shoots from the rhizome appeared in many, but not all locations where the aerial shoots were severely damaged. At those sites where new shoots did not appear, perhaps the Pacific waterleaf decided to save its buds, and energy, for next year.

And for some plants, it’s the end of the line!

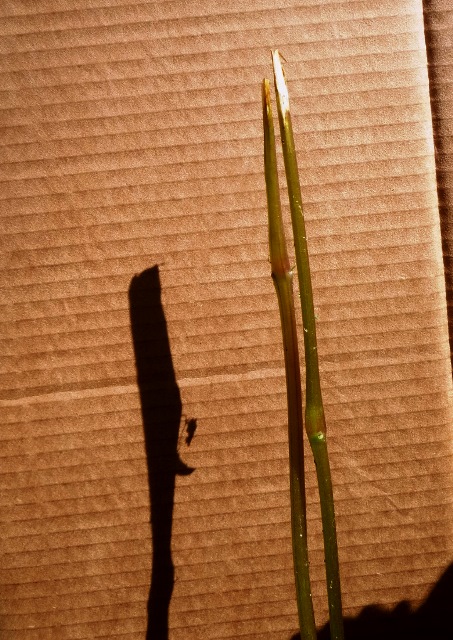

Some plants never did recover from the hailstorm. The best example is the jewelweed, an annual plant that grows mostly along the creek. The two jewelweed plants pictured below had their tops broken off, and were stripped of all leaves. While the stems managed to stay alive throughout the summer, this is not recovery!

As annual plants that must start from seed each year, jewelweed did not have buds already formed for next year which it could call upon to elongate early. As mentioned in my earlier Naturalist’s Note, the jewelweed will have to rely upon two things; the fact that viable jewelweed seed can be “banked” in the soil for a couple of years, and the fact that not all the jewelweed plants were damaged as heavily as these two individuals.

From an overview perspective, there were substantially fewer jewelweed flowers this year than the last two years. Only more time will tell how serious this setback was for the species at Tryon Creek.

The Forest Survived!

Overall, the forest appears to have come through the hailstorm in good shape. Given the long run of history, this probably isn’t the first hailstorm these species have endured. The plants that couldn’t cope with this type of abuse died out long ago. It’s the old story, survival of the fittest! As you walk the trails at Tryon Creek, take pride in knowing that you walk among “Nature’s finest!”

The Rocky Road…

The Rocky Road to Reproduction

By Bruce Rottink, Volunteer Nature Guide and Retired Research Forester

Ah, spring! A time when plants at Tryon Creek State Natural Area are in bloom, with the promise of new generations of plants to come. Or not! While beautiful flowers are a vital step to a new generation of plants, it’s a rocky road to reproduction. If we follow through the process of plant reproduction, we see that the obstacles are numerous. Failure to reproduce is such a common result that every living plant at Tryon Creek is something of a miracle.

But let’s start at the beginning.

Each plant must first initiate a flower. For many species, for example, Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and trillium (Trillium ovatum), this takes place the summer before the flowers appear. Each year a significant percentage of individual plants never form a flower. This is often the case if, for example, a plant is growing in a shady location, which just barely meets the needs of plant survival.

Or…

Perhaps the plant had an abundant crop of flowers the year before, and the plant’s reserves were drained in that effort.

Or…

Perhaps the weather conditions last year were not very good for initiating flowers.

Below is a picture showing a trillium that just did not produce a flower this year. Every year at Tryon Creek SNA, there are LOTS of trilliums that don’t produce a flower.

So they won’t be reproducing!

But let’s suppose a flower is initiated. That’s a nice start, but there’s still a long way to go. This spring I noticed several of Tryon Creek’s low Oregon grape (Mahonia nervosa) that had produced a flower stalk and flowers (an inflorescence), but it never actually opened up to show flowers. It dried up and died before it got to that point.

The picture below is of a low Oregon grape inflorescence that started to develop, and then for some reason, died.

But even if the plant has produced an inflorescence and it’s opened up to expose the flowers, many hazards still await. The weather can turn deadly. A late frost or an extra-dry spring can mean the end for flowers that have already emerged. And that’s not all, the picture below shows some bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum) flowers laying on the Old Main Trail that got blown out of a tree by a spring windstorm!

Well, they’re never going to produce seeds.

So suppose a flower has developed, opened and escaped the usual weather-related problems. That’s a good start, but that’s not the end of the story. In trilliums, like most other plants, seeds are produced only when pollen (produced by the male parts) lands on the stigma (the sticky female part of the flower) to fertilize the ova (egg). In trilliums, as in many plants, the male and female parts are found in the same flower.

Trilliums, like lots of other plants, can’t be fertilized by pollen from themselves, they need pollen from a different plant.

Here’s the bad news:

So much pollen is produced by each flower that scientists believe sometimes the flower’s own pollen completely covers the female stigma blocking pollen from other plants. Last year I did a survey of 88 trilliums at Tryon Creek State Natural Area along a portion of two trails. Of 88 trilliums that had produced flowers, only 33 produced any seeds! That’s just 37-1/2% of the flowers that produced seeds! Now before you get alarmed, this is about the same percentage of success that scientists have reported for trilliums in other areas. At this time of year, you can see the fat green seed pods on the successful plants (photo on the left), and the tiny brown dried up seed pods (photo on the right) of the flowers that failed.

Whew! What a struggle it’s been so far! But there’s still a couple more hurdles to go.

So suppose you’re a plant that’s managed to produce some seeds. Seeds are little packets stuffed full of high energy starches or fats that help young plants get a good start in life. Oh-oh! Turns out there are lots of critters at Tryon Creek that are interested in packets of high energy (the “seeds”!)

Can you guess who?

Douglas squirrels, spotted towhees, mice, and more! We can see the tragic (for the seeds!) end results in every squirrel midden where a squirrel has chewed apart a Douglas-fir cone and eaten all the seeds.

In the picture below, you can see the central axis (“stalk”) of the cone in the upper left part of the picture, surrounded by the pile of cone scales.

Oh no! They were so close to success.

Fortunately, there is a bright side.

Every year there actually are some seeds that survive the whole gauntlet. These seeds fall to the ground and germinate early in the spring, producing new plants.

Here is a close-up of one new maple germinant:

And some more hope for seeds

Here is a picture of a whole cluster of brand new bigleaf maple seedlings ready to grow up and become the queens of the forest.

There are more than 40 new trees started.

Unfortunately…

The photo below, taken just 4 weeks later, shows that all the new seedlings have been wiped out! Maybe the weather got too dry, maybe the soil was a little too hard for the roots to penetrate, or maybe a hungry mouse stopped by.

Whatever the reason, it’s the end of the road for those little maples!

It’s a rocky road to reproduction, but once in a great while a plant makes it all the way, like this majestic Douglas-fir near Old Main Trail in the photo below.

When you understand all the barriers to successful plant reproduction, it’s a lot easier to think of each and every plant as a miracle! The next time you’re at Tryon Creek, take a good look at all the plants around you! These are the survivors, the ones that were both lucky and tough!

Quirky “Quadliums”

Mother Nature’s Mistakes: Trilliums, Quadliums, and More

By Bruce Rottink, Volunteer Nature Guide

Have you ever had a day, when you were so tired, that you started making mistakes? When you look around, and see some of Mother Nature’s mistakes, you begin to wonder if maybe she gets tired too.

At Tryon Creek State Natural Area you can see many of Mother Nature’s mistakes. Everyone knows, for example, that trilliums (Trillium ovatum) have three petals, like the picture below. That’s why they’re called trilliums; the “tri” stands for “three.”

“D’oh!”

But when you pay attention, you see that every now and then there is a trillium that doesn’t quite follow the rules, like this trillium I found on Middle Creek Trail. Four petals! So is it a quadlium?

Not only does it have 4 petals, it has four leaves too!

As if that’s not weird enough…

Take a close look at the number of stamens (those long fuzzy yellow things that make the pollen) and the number of styles (the white things in the very center that look like tiny, curved octopus arms, which are female parts of the trillium). A normal trillium has six stamens and three styles, but not this one!

Curiouser and curiouser

How about this trillium (pictured below) that popped up along Old Main trail a couple of years ago with two conjoined ovaries; six stamens and six styles, instead of the normal three styles.

It doesn’t end there

Later on in the season, this flower produced a conjoined pair of seed capsules.

Compare the normal seed capsule on the left to the capsule which developed from the two conjoined ovaries on the right.

Any guesses as to why?

These “mistakes” aren’t necessarily genetic mutations, but might be just developmental anomalies. Developmental anomalies are the result of abnormal things that happened during plant development. The anomalies can be the result of a variety of environmental factors, like water stress or cold shock, or even an infection with certain types of bacteria or plant viruses.

And more…maple mishaps

Mother Nature’s mistakes aren’t limited to trilliums. Normally, the seed of the bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum) is born in pairs, as you see in the picture on the left.

However, on occasion, the seeds will be produced as triplets, as you see on the right.

1 in 500

During a recent check at Tryon Creek, I found that slightly less than 1 in 500 maple fruits was a triplet. All the rest were double-seeded. However, keep your eyes open; years ago in the Oregon coast range, I found a bigleaf maple fruit consisting of 7 seeds all joined together.

These oddities are interesting of course, but can they do more than just gratify our idle curiosity?

Yes! As Francois Jacob, winner of the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine said,

“One of the most effective ways of determining the normal mechanisms of the cell is to explore abnormalities in suitably selected monsters.”

By “monsters” of course he meant abnormal specimens. For example, if we only looked at normal trilliums, or even the four-petaled trillium, we might conclude that there was some process in the plant which ensured that there were always twice as many stamens as styles. However a single glance at the trillium with conjoined ovaries shows that isn’t true.

So if you think you’ve “seen it all” at Tryon Creek, just keep your eyes open for more of Mother Nature’s “mistakes.” They open up a whole new world of wonder.