Blog Archives

Trillium Trivia

By Bruce Rottink, Volunteer Nature Guide & Retired Research Forester

Western trillium (Trillium ovatum) flowers are a major attraction at Tryon Creek State Natural Area (TCSNA). I’ve already written three Naturalist Notes about this plant. In the process I’ve accumulated a host of materials that didn’t fit too well with any of those previous notes; the time has come to share them.

How big do trilliums grow?

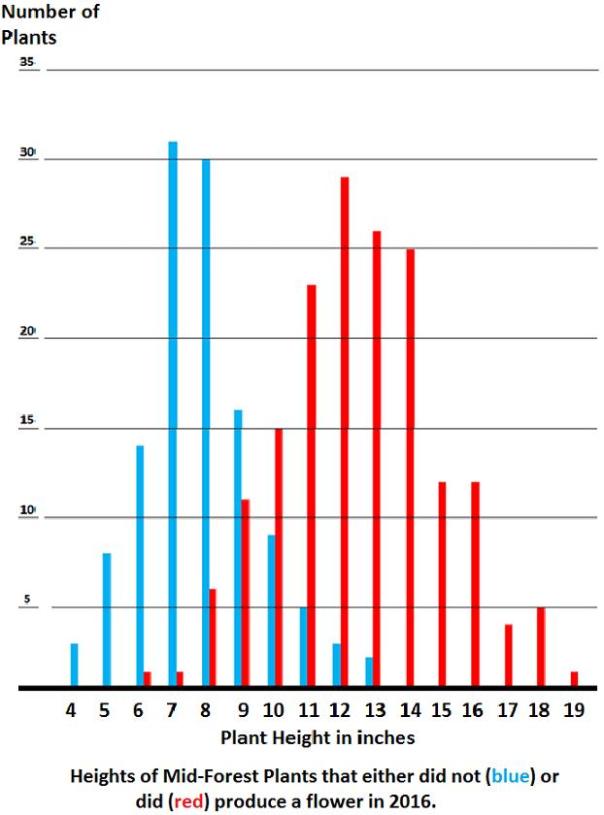

From May 4 through May 6, 2016, I conducted a survey of trilliums that were growing more than 10 feet from any trail. The areas I surveyed were near the Equestrian and North Horse Loop Trails in the northern part of the park, Center, Big Fir and Old Main Trails in the central part of the park, and Iron Mountain Trail in the southern part of the park. For each triple-leafed trillium I encountered I measured the distance from the ground to the attachment point of the triple “leaves.” I also noted whether or not each plant was flowering. The results are shown below.

Ten inches is about the height where the plants shift from non-flowering to flowering, although a couple of very short plants flowered, and a few fairly tall ones didn’t.

What happens to the trillium’s flowers and seed pods?

Ideally, the flowers are pollinated, the seed pods (or capsules) mature, then open and release their seeds into the forest. Of course there are other possibilities. Deer, it has been reported, sometimes eat the flowers. The contents of the maturing seed pod are very nutritious, and researchers have reported that both deer and mice sometimes eat the seed pods.

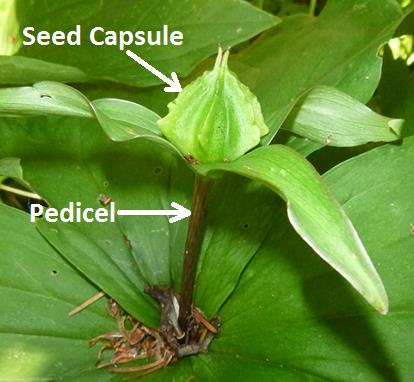

To assess this, I conducted surveys in two different years. The first survey was conducted between June 23 and 28, 2015. Two groups of trilliums were surveyed. “Trailside trilliums” were those growing within 10 feet of the trail. “Mid-forest trilliums” were those growing more than 10 feet from the trail. It should be noted that at this time the seed pods are well along the path to maturity. The plants were placed in three categories: a) capsule intact, b) pedicel only, meaning the plant had flowered, but the flower/seed capsule was missing, and c) did not flower, as indicated by having no pedicel or capsule. Illustrations of each class are below:

Capsule intact

Pedicel only

Did not flower

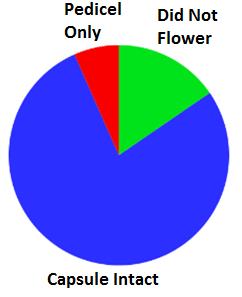

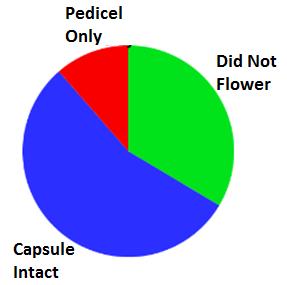

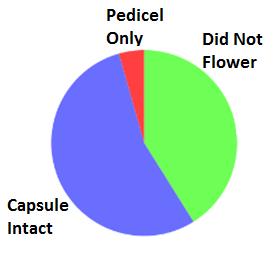

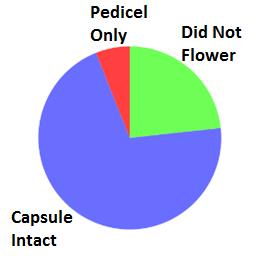

The results are shown below:

Plants within 10 feet of trail

Plants more than 10 feet from trail

A statistical analysis (Note to nerds: I used the Chi-squared test.) clearly shows that a significantly higher percentage of the trailside plants flowered compared to plants growing more than 10 feet from the trail. The cause of this difference cannot be determined by this study. The other statistically significant difference between these two groups is that a higher percentage of the “mid-forest” trilliums only had a pedicel (“flower stalk”), which means that either the flower or the seedpod was removed. Animals likely ate these seed pods or flowers. Perhaps the deer are more comfortable eating in the middle of the forest than trailside.

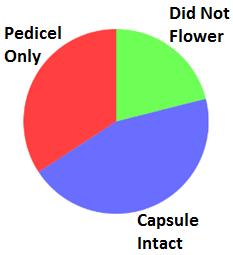

In 2016 I undertook a second trillium survey, this one was conducted May 4 through May 6, at a time when the last of the trillium petals had just recently fallen off the plants. This time, however, the “trailside plants” I tallied were within 3 feet of the trail. The “off-trail plants” were growing more than 10 feet from a trail. At this time the seed capsules were small and immature. The results are shown below:

Off-trail plants

Trailside on Cedar, Red Fox and Middle Creek Trails

Trailside on Old Main

Once again, the percentage of plants flowering was statistically significantly higher in the trailside plants compared to plants growing “off-trail”. A slightly smaller percentage of the flowers/seed-capsules had been eaten than in the previous study, probably because there was a shorter period of time for the animals to eat them, or perhaps, being smaller, they were of less interest to the animals. The one thing that clearly stood out in the data is that the percentage of reproductive structures missing was significantly higher along Old Main Trail than along the other trails. (Geek note: Statistically, there is less than a 1 in 10,000 probability that the higher percentage of missing capsules observed along Old Main was due to chance.) The fact that Old Main is one of the most heavily traveled trails makes it tempting to speculate that people were picking these flowers, as shown in the picture below, but this study cannot prove that.

Freshly plucked trillium flower lying on the trail.

An alternative explanation for the empty pedicels is that the flower was defective and the defective bloom was aborted. I recently saw a single dysfunctional bloom in the forest. It appears that the plant started to produce a functional flower, but something bad happened along the way, as in the example below, where you have what appears to be an attempt at a flower, but no actual petals.

“Failed” flower on a trillium plant.

Does it really take 7 years for a trillium to recover after the flower is picked?

Many people believe that if you pick a trillium it will be 7 years before the plant flowers again. I unexpectedly got a chance to test that theory when someone picked 6 trillium flowers on a plot of trilliums I had been studying for 5 years. I concluded these had been picked, because the remaining stems did not exhibit the type of cut associated with animal browsing. One of the stems from which the flower had been picked is shown below:

Stem from which trillium was picked.

Although very unhappy, I decided to capitalize on the tragedy. (“When life hands you a lemon, make lemonade!”) I carefully documented the exact location of the trilliums. Based on the location of the six flowers, it appeared that all of them were twin stems, arising from a total of only three rhizomes (rhizomes are like a flower bulb).

In April 2017, one year after the tragedy, I surveyed the site again. I went to the site and measured the location of the trilliums. Based on their location, 2 flowering stems were within ½” of the location of the flowering stems that were decapitated last year. Thus I concluded that only 2 out of the 3 effected rhizomes produced flowering stalks again this year. However, whereas last year they were twin-stalked, this year they only had one stalk each. At the location of the third picked trillium, there was nothing. Scientists have determined that some years a trillium will occasionally just take a rest, and not produce an above ground stem. So that is what this one did, OR it died. I don’t know which. Either way, for at least two of the plants, the “7 year” myth is debunked.

Does anything eat trilliums?

Deer are commonly reported to eat trilliums. But it turns out that isn’t the whole story. This spring I ran across one of our slimy forest friends deeply engrossed with a trillium. Note that this is not our native banana slug (Ariolimax columbianus) but appears to be one of the non-native species.

Slug in a trillium flower

You’ll notice that considerable chunks of the trillium petals are also missing, and these may only have been the prelude to the slug’s full scale attack on the heart of the trillium flower.

What pollinates trilliums?

Most of the plants we hear about are pollinated by bees, like our Pacific waterleaf (Hydrophyllum tenuipes), or by the wind, like Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). Trilliums are a little different. A study of Trillium ovatum in southern Oregon determined that pollinators included several species of beetles, honey bees, bumble bees, crab spiders and geometrid moths1. Since the trillium doesn’t produce nectar, at least some of these creatures are here to eat the pollen, and they spread the pollen as an unintended side effect.

Pollen-coated insect in a trillium flower

Pollen-carrying stinkbug in trillium flower

Unidentified insects (the “brown things”) converging on a trillium flower

The lesson…

The forest is endlessly fascinating, when a person just stops to observe. Looking back on my old trillium photos, I now see lots of the “little brown bugs” deep down in the bloom. How could I have missed that so often? When you’re out in our forest, stop for a minute and look around. I think you’ll be amazed, as I was, at how many interesting things are out there.

_____________________________

1Jules, Erik S. and Beverly J. Rathcke. 1999. Mechanisms of Reduced Trillium Recruitment along Edges of Old-Growth Forest Fragments. Conservation Biology 13:784-793.

Trilliums: The Dark Side

By Bruce Rottink, Volunteer Nature Guide & Retired Research Forester

At Tryon Creek State Natural Area (TCSNA), springtime is trillium (Trillium ovatum) time. Walking through the forest, who wouldn’t be delighted by these tough, brown, lumpy trilliums that look eerily like a piece of poop (“feces” for the delicate among you)? Surely something we can all….. What? Oh, I’m sorry! I forgot that you’re used to only seeing the parts of trillium that are above ground. Well then fasten your seatbelt pilgrim, ‘cuz today we’re taking a dive into the dark side. Thanks to an anonymous donor with hordes of trilliums in their private forest, we’re going to look at the part of the trillium that’s underground!

What’s Down There Anyway?

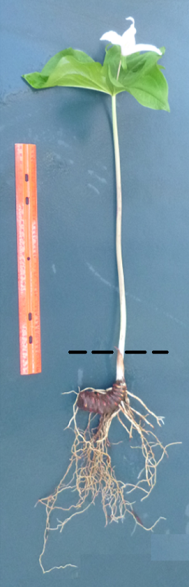

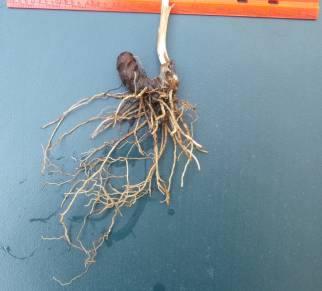

Pictured below is a whole trillium. The level of the soil is marked with the black dashed line. Above ground is the familiar white flower, the large green leaves (which are technically “bracts”), and the long stem (in botanical terms it’s actually a “scape”). As you can see, the two main things underground are the large, lumpy brown rhizome and the stringy white roots. When straightened out, the roots are about 30 cm (1 foot) long. I excavated this plant very slowly and carefully. The vast majority of the roots survived the extraction process, although there was some minor root breakage in the process. The orange ruler is 12 inches (about 30 cm) long.

Complete trillium with an orange 1 foot (30 cm) ruler. The ground-line is represented by black dashes

The photo below gives a close-up view of only the subterranean elements of the trillium. The two principle parts are the profusion of whitish roots and the thick brown rhizome.

Rhizome and root system of a trillium

In the close-up photo below, the roots look pretty unremarkable. However, they do seem to branch less than many species I’ve observed. You might notice that the roots don’t originate evenly over the length of the rhizome, but rather are concentrated on the right-most end of the rhizome which bears the scape (stem) of the plant. This is the younger end of the rhizome. The left (older) end of the rhizome bears very few roots. Also notice the abrupt, rather than tapering, left end of the rhizome. It almost looks like the older (left) end of the rhizome has been cut off. In fact, as the rhizome ages, the oldest part of the rhizome is decayed away, leaving a flat end.

Cool, but how old is this trillium?

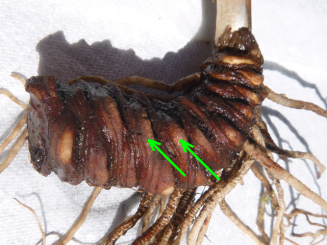

People have long been fascinated with the question of how old a particular trillium is. They have attempted to determine the age of a rhizome by counting leaf scars. The green arrows in the picture below are indicating just two of the “lumps” which are the leaf scars. The fact that the older end of the rhizome keeps decaying away is just the first of two major hurdles to correctly aging the plant.

The older (left hand) end of the trillium rhizome terminates abruptly. Green arrows point to leaf scars.

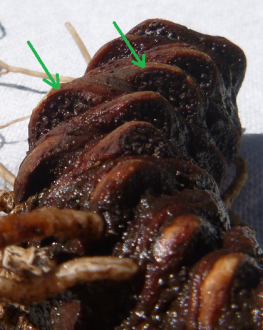

A view down the rhizome from the young end of the rhizome gives a different, and perhaps more instructive view of the leaf scars. From this perspective each of the leaf scars is a little shelf, with the leaf coming out of the flat top side of the shelf. The top of each shelf appears to be full of some “knobby” structures, which I have cheerfully assumed are the healed-over stubs of the vascular tissue (like veins) that connected the leaf to the rhizome. The green arrows point to individual shelf-like leaf scars.

Looking down along the side of the rhizome. Green arrows indicate two leaf scars.

It has been widely assumed that by counting the leaf scars you could determine the age of the plant, much as you might count tree rings. If the trillium produced only a single stem (scape) per year, this would be a wonderful system. Sadly, it is not so simple. This is the second major hurdle to aging a trillium plant by counting leaf scars. Namely, that the trillium can produce more than one stem per year, and thus more than one leaf scar per year. The example used above produced one leaf this year. However, another trillium, which I had growing in a pot in my backyard, is pictured below. Clearly it has produced two stems (scapes) this year, and thus will leave two scars in the future. As a side note, you can see that both of these stems blossomed.

Trillium which produced more than one leaf this year. Photos left to right showing increasing level of detail.

The rhizome of the trillium I dug out of the forest has, as near as I could determine, 45 leaf scars. Assuming that each year it produced either one or two leaf scars, it is somewhere between 22 and 45 years old. But that’s just the part of the rhizome that hasn’t rotted away yet. So much for being able to determine the age of trilliums!

So what does the rhizome do?

One of the rhizome’s main functions is as the food storage organ for the plant. The huge amount of energy stored in this rhizome over winter is the reason trilliums shoot up so quickly in the spring. The trilliums don’t have to manufacture food as they burst up from the ground. Instead they draw upon the massive food reserves already in the rhizome. Below is a longitudinal (“lengthwise”) cut through the rhizome. This rhizome is approximately 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter. The inside has approximately the feel and texture of a potato. Of course after the spring burst of growth, the green parts of the trillium above ground take on the task of replenishing the food reserves for next year’s scape, bracts and flowers.

Interior of a trillium rhizome

The trilliums of TCSNA are probably a lot older than we first imagined. They are not only the Princesses of the Forest, they are tough, long-lived members of our forest community.