Blog Archives

Fighting Flora

The Plants Fight Back!

By Bruce Rottink, Volunteer Nature Guide and Retired Research Forester

Plants may seem like passive members of the Tryon Creek State Natural Area (TCSNA) forest community. They stand in one place for many years, stoically enduring every insult the ecosystem throws at them. Their reactions are neither flashy like birds, nor noisy like squirrels. Their efforts at survival are more subtle, yet often very effective.

Plants are subject to a wide range of diseases, primarily caused by fungi or bacteria. Unlike many animals, plants don’t have an immune system to fight off infections. Still, over many generations, plants have developed some defensive tricks that might not be obvious to humans.

Okay, how do plants cope with infections?

One method of dealing with disease is to just give up and start over again! For example, by early August of 2013, all the leaves of one particular vine maple (Acer circinatum) near Obie’s Bridge were heavily infected and damaged by a microorganism. The photo below shows the extent of damage to typical leaves.

Heavily infected leaves on a vine maple

Damaged as the leaves were, the plant reacted by dropping all of the diseased leaves in early August, and growing a new set of uninfected leaves. The uninfected leaves served it well through the remainder of the growing season. The new leaves are shown in the photo below. You’ll note in the photo that the leaves on the lower portion of this branch have not yet grown out, and may not grow out this year.

Second set of leaves in a single year

Wow, that seems like overkill!

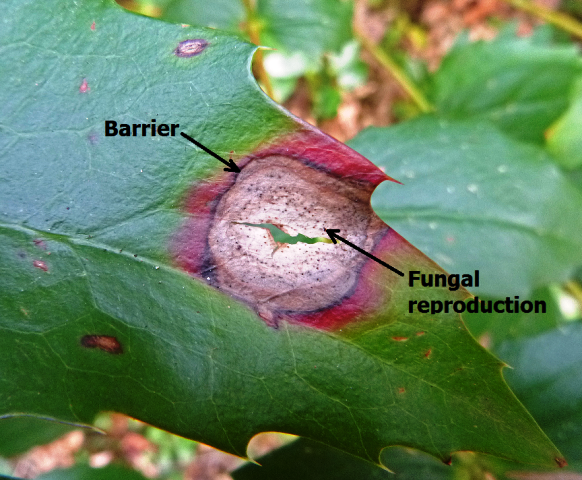

Yes, this is a radical approach to dealing with leaf diseases, but when all other defenses fail, the plant has little choice. More often, plants deal with leaf infections by a process known as “compartmentalization.” This is illustrated in the photo of the Oregon grape (Mahonia sp.) leaf below. This leaf has been attacked by a fungus. The fungal attack has killed the leaf tissue, as indicated by the pale circular (and now fractured) area of leaf tissue. In response to the infection, the leaf has created a barrier, seen as a thin black line, to stop the infection from spreading. The black spots within this area are places where the fungus has produced spores.

Fungal infection on Oregon grape leaf

Actually, the leaf has responded to the fungal attack in two ways. First, it has created a physical/chemical barrier to the fungus, which is the black ring surrounding the infected spot. This will stop the fungus from spreading any further into the leaf. Secondly, the reddish areas of the leaf are colored by the natural chemical called anthocyanin. Scientists have discovered two very cool things about anthocyanin. First, scientists have shown that anthocyanin interferes with the growth of fungus. Second, scientists have discovered that many plants start producing anthocyanin when they sense a fungal infection. So the production of anthocyanin is the plant’s form of chemical warfare, triggered by the presence of fungus.

In the interests of full disclosure, the anthocyanin may “appear” for one of two reasons. First, it may have been there all along, and only becomes visible when the normal green pigment (chlorophyll) disappears. Or secondly, it may have been synthesized by the plant in response to the attack. While it is not definitive proof, the photo below of a leaf attacked by fungus shows the (red) anthocyanin only near the region of fungal attack. This in spite of the fact that the chlorophyll has disappeared from the leaf. This suggests to me that the leaf was not filled with anthocyanin that was revealed when the chlorophyll disappeared, but rather the anthocyanin was specifically synthesized in response to the fungal attack.

Senescing leaf of Oregon grape

What happens when decay gets into a tree’s trunk?

When a tree is dealing with a fungal attack on its main stem, or trunk, just giving up is NOT an option. Once wood has started to decay, it doesn’t “heal.” And plants, as far as we know, don’t have immune systems. So instead, the tree uses the same compartmentalization technique as it uses with leaves. It isolates the fungus to make sure it doesn’t spread throughout the entire tree trunk.

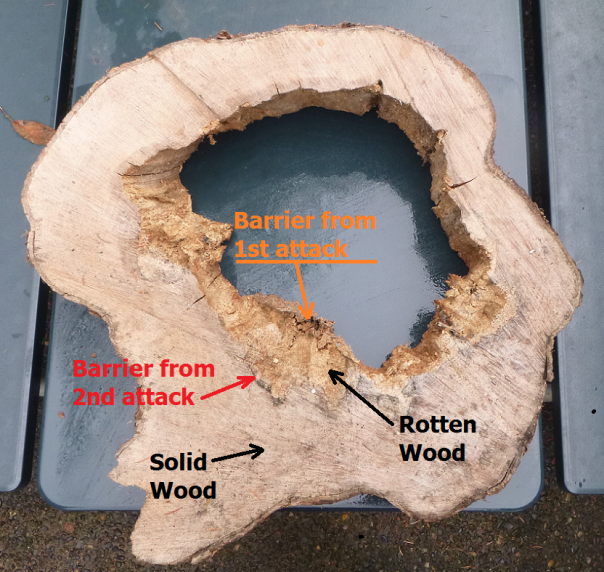

Below is a picture of the cross section of an alder (Alnus rubra) tree that was growing near the Tryon Creek Nature Center. It was cut down because it was a hazard to folks using the park. The picture clearly shows the solid reddish-brown wood, the gray-ish area of rotten wood probably caused by a fungus, and the thin black barrier the tree has developed to compartmentalize the infection.

Cross section of a red alder which has compartmentalized fungal rot

Park Ranger Dan Quigley found another very interesting rotten tree while cleaning up some “tree messes” around TCSNA. He cut me a “tree cookie” (a cross-sectional slice of the main trunk) and hauled it back to the shop. THANKS, DAN! This specimen of bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum) is interesting in that this tree appears to have been attacked by rot twice. It probably was wounded and infected once, and then sometime later, it was wounded and infected again. In older trees this is not uncommon. Again the black lines are the barriers created by the tree. (For size purposes, note that the tree cookie is overlapping both edges of the 29” wide picnic table it is resting on).

The wood at the very center of the tree, inside the first barrier, was so rotten that it has disappeared (probably in the cutting/handling process, if not prior to that). Most of the barrier was destroyed too. However, one small section of the first barrier is still present.

Slice of a hollow bigleaf maple trunk from TCSNA

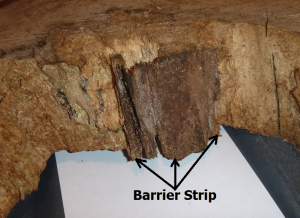

This specimen provides a rare opportunity to view the “barrier” up close. I scraped away some of the rotten wood inside of the 1st attack barrier. The photo below shows a side view of the barrier, with the barrier being a darker color than the rest of the wood.

Side view of one section of the barrier strip in a partially rotten tree trunk

I carefully dug out some of the rotten wood between the first barrier strip and the bark. Then I took the photo below looking pretty much straight down the tree trunk. In this photo, you can see that the barrier strip is a real physical entity. It is approximately the thickness of, and as strong as, the material in a standard manila file folder.

Looking from the top down at the tree’s barrier to the 1st attack

Plants are tough!

Plants are rich storehouses of the energy that fungus and other disease-causing organisms need for their own success. Plants are under constant attack. While their defense mechanisms generally allow the whole plant to survive, it is often at the cost of sacrificing a part of themselves to the disease. Somehow, both the plants and the fungus have survived for millions of years, making our forest the home to some of the toughest organisms that you can imagine.

* Thanks to Jay W. Pscheidt, Extension Plant Pathology Specialist and Professor of Botany and Plant Pathology at Oregon State University for his input on this post. He both confirmed some things I thought I knew, and provided some new information on this topic! This exemplifies one of my favorite quotes, “None of us is as smart as all of us!” That said, I take full responsibility for any errors in this note! — Bruce Rottink